Objectives and Key Results

A framework to navigate in a complex world

Objectives and Key Results (OKR) as a framework promises more focus, transparency and above all alignment in an organization. Within the last decade, the popularity of OKR has grown rapidly and its use in organisations has become indispensable.

This is because Objectives and Key Results enables a customer-centric mindset by focusing work on the impact and resonance generated with the target audience, rather than just the speed of implementation.

In addition, OKR, when used properly, encourages continuous strategy development and implementation to become part day-to-day work of everyone involved in an organization.

This guide highlights the benefits and principles of OKR and describes how to apply the OKR framework in an organization.

1. What is OKR?

Objectives & Key Results is a framework that helps organisations implement a vision and strategy by aligning everyone to channel their capacities, focus on prioritised goals, collaborate in short iterations to validate assumptions as quickly as possible, and learn through measurable outcomes to continuously adapt their strategy and tactics.

Objectives and Key Results (OKR) provide guidance to navigate through complexity by making abstract topics tangible and verifying hypothesis through measurable results to review if and how the chosen path is still the right one.

”We start our journey to our dreams by wanting, but we arrive by focusing, planning and learning.”

Christina Wodtke, Radical Focus

OKR consists of two elements that are to be considered as a set and should not be separated from each other.

- Objective is a qualitative description of a timeboxed goal that intends to implement a strategy.

- Key Results are quantitative descriptions that make the achievement of the objective measurable.

OKR Examples

- Objective: Customers can use the product across all platforms.

- Key Result 1: Usage on mobile devices increased by 50%.

- Key Result 2: Daily Active Users (DAU) increased by 30%.

- Key Result 3: Users on mobile devices are 50% more active.

- Objective: We create awareness around the topic “Diversity in companies”.

- Key Result 1: 30% of website visitors return within 5 days.

- Key Result 2: 10% of website visitors contact us for more information.

- Key Result 3: The campaign hashtag gets mentioned 5000 times.

The origin of OKR goes back to the 1950s. Peter Drucker’s method “Management by Objectives” (MbO) was used in several companies, including Intel. When Intel was struggling with economic problems in the 1970s, Andy Grove, then CEO of Intel, decided to adapt the existing management system to increase the adaptability of his company.

Annual objectives became quarterly objectives to define a clear direction and focus with short-term objectives that always fit the current circumstances. Grove also added measurable key results to make the progress more tangible and transparent. This adapted form of MbO is considered today as the origin of OKR.

John Doerr, then an Intel employee, later an investor in Silicon Valley, introduced the OKR framework to Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin in 1999, and Google has been working with OKR ever since.

In 2013, Rick Klau, then YouTube product manager, published a video in which he explained how Google works with OKR. Ever since, countless renowned companies worldwide have adopted the OKR framework. Not only large companies such as Amazon, Spotify, Netflix, Slack, Daimler, Bosch, Telekom, but also many start-ups as well as small and medium-sized enterprises worldwide use OKR today.

Through its use in different business contexts and thanks to the expertise of some influential people around the world, OKR continues to evolve, so that Andy Grove’s original idea of output management has today been heavily modified in the direction of “outcomes” (see section 3.3.).

Benefits of OKR

- Focus: The conversation around OKR creates clarity about what is most important in the current situation and what is not. Questions like “what for”, “why”, “why now” challenge everyone involved to dig deep, create mutual understanding of current circumstances and then decide together what to focus on next.

- Alignment: Connecting the day-to-day work to organisational success ensures organisation-wide cohesion and adds meaning to one’s work.

- Commitment: OKR promotes structures to enable “aligned autonomy”, which helps to increase intrinsic motivation and employee engagement.

- Trackability: Measurable results are used to continuously check and discuss objectively whether the selected initiatives and activities are helpful or need to be reconsidered.

- Stretch: Ambitious goals push limits and create a space for experimentation where creative and innovative ideas can emerge.

2. Why OKR?

Most of the management concepts currently in use solve problems of “yesterday”, when efficient mass production was the biggest challenge in the transition from small local markets to larger markets. But since the liberalisation and globalisation of markets in the last decades of the 20th century, and especially since the internet connects the world with one click, distances no longer matter. Local markets have become a global village. This phenomenon has drastically changed the way we think, consume and communicate. However, the way we work has not yet been adapted. At least not sufficiently.

“Probleme kann man niemals mit derselben Denkweise lösen, durch die sie entstanden sind.”

Albert Einstein

Many companies spend weeks or months preparing AOPs (Annual Operating Planning), roadmaps or project plans for the next one to three years. Such detailed planning of ready-made solutions suggests that the right solutions are already known and the internal and external factors that influence implementation and results are under control.

And although year after year it is then repeatedly proven that these plans have at best a validity of three to six months, these practices are repeated every year.

Why? Because it gives a (false) sense of security and control.

“The most important thing is to know what you can’t know.”

Marc Andreessen, Mitbegründer von Netscape

Is there a way to have a sense of security and control without meticulously pre-planning everything?

Yes, there is! However, for this to happen, the volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA) of our time must be acknowledged and it must be accepted that it is not possible to know or predict all the solutions and answers in advance. Working with hypotheses, like scientists, should become the new norm of all organisations.

In complex contexts, as Dave Snowden describes in the Cynefin Framework, the relationship between cause and effect is not known in advance and can only be analysed in retrospect.

The higher the uncertainty, the higher the risks of backing the wrong horse. For this reason, it is economically advisable in complex environments to keep the implementation effort as low as possible until the added value of the idea has been validated. Since the knowledge of experts alone is not sufficient for complex problems, it is necessary to work in short iterations with “safe to fail” experiments (probe). Afterwards, hypotheses can be validated (sense) in order to derive the next steps from what has been learned (respond).

The Probe-Sense-Respond way of working is the core of the OKR framework and can therefore be the life buoy for complex challenges. Working in short OKR cycles (three to four months) through experimentation (Probe), measurement (Sense) and reflection (Respond) encourages a way of working with “hypotheses” rather than “ready-made solutions” and enables adaptive implementation of the strategy.

The higher the uncertainty, the higher the risks of backing the wrong horse. For this reason, it is economically advisable in complex environments to keep the implementation effort as low as possible until the added value of the idea has been validated.

Tweet

3. How to write OKR?

An OKR set consists of one objective with two to three key results per objective. Both elements provide different information that complement each other. Therefore, objectives and key results should not be considered separately, but only together do they create a complete description of the goal statement.

OKR sets are ideally defined every three to four months. To create focus, the number of OKR sets should be limited. Following the motto “Start less, finish more”, it is recommended to define a maximum of three OKR sets (3x objectives and 2-3 key results per objective), because only completed solutions can generate added value.

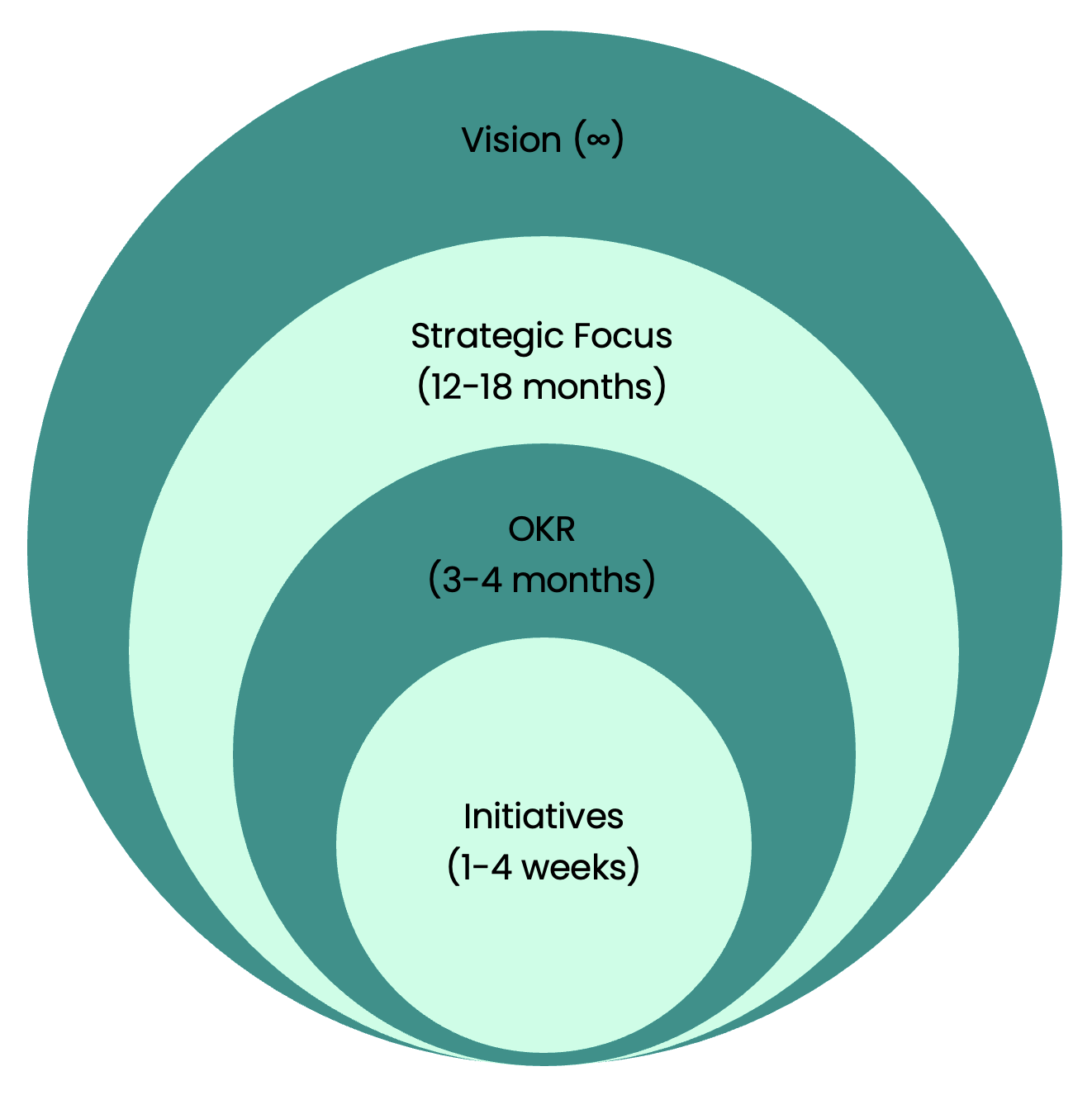

Before explaining the definition of objectives and key results, it is important to understand at which working level, for whom and for what purpose OKR sets provide valuable information. OKR sets are used as a link between vision and strategy and their implementation.

Vision and strategy are therefore prerequisites for effective OKRs, just as OKR sets are prerequisites for the definition of initiatives or an action plan.

Important: Transparency is an indispensable principle when working with OKR. In order to establish a vertical (top-down – bottom-up) and horizontal (cross-team and cross-divisional) alignment between vision, strategy and implementation, all information (vision, strategy, OKR sets, initiatives) must be freely and unrestrictedly accessible to all.

Vision and strategy are therefore prerequisites for effective OKRs, just as OKR sets are prerequisites for the definition of initiatives or an action plan.

Tweet

3.1. Strategic Focus

While the vision is indispensable information and source of inspiration, it is usually quite abstract, so there is a lot of room for interpretation, which can cause teams working in totally different directions. To ensure that all forces are channelled in the same direction, and that the short-term OKR sets (3-4 months) from different teams move in the same direction, a tangible strategic goal for a foreseeable future (12-18 months) is needed so that strategic alignment and focus can be established.

In practice, it has often been witnessed that the usual Business KPI dashboards, Strategic Pillars with evergreen statements are not sufficient for true strategic alignment. Instead, the Mid-Term Strategic Goal should provide concrete answers to two central questions that Roger L. Martin asks in his framework “Playing to Win”: “Where to play” and “How to win”.

The mid-term strategy should be a synthesis of continuous market observations, analyses and contact with customers and describe a hypothesis on how customer needs or problems and market trends could create competitive advantages.

The core content of a strategy is a diagnosis of the situation at hand, the creation or identification of a guiding policyfor dealing with the critical difficulties, and a set of coherent actions.”

Richard Rummelt, Good Strategy, Bad Strategy

The mid-term strategy should be directional and create focus without saying exactly what needs to be done and at the same time exclude what should not be done. The strategic clarity helps the participants to make autonomous decisions later in the OKR process and thus reduces the need for micro-management.

The Mid-Term Goal should be a synthesis of continuous market observations, analyses and contact with customers and describe a hypothesis on how customer needs or problems and market trends could create competitive advantages. It should be directional and create focus without saying exactly what needs to be done and at the same time exclude what should not be done. The strategic clarity helps the participants to make autonomous decisions later in the OKR process and thus reduces the need for micro-management.

Tweet

This customer-centric and qualitative mid-term strategy could be made measurable through quantitative metrics. In addition to the usual business KPIs, such as sales and market share, the so-called North Star Metric is an ideal complement, representing the core value that a product should offer to its customers.

In the “North Star Playbook”, John Cutler describes the North Star Metric as follows:

“North Star Metric is a single critical rate, count, or ratio that represents your product strategy.”

John Cutler, North Star Playbook

North Star Metric Examples:

- Netflix: The number of subscribers who watch more than X hours of content per month.

- Airbnb: Booked nights.

- Spotify: Time that a user spends listening.

3.2. Objective

An Objective is derived from the mid-term strategy and is a qualitative description of a desired target state. Objectives provide orientation and are activating by being motivational and aspirational.

An objective describes a concrete change that delivers added value for a specific target group and can be visibly experienced at the end of an OKR cycle. The objective is defined by the team itself, which can also work on it and implement it autonomously within the next 3-4 months.

Objectives Checklist

- Qualitative and directional

- Motivating

- Activating

- Describes added value for a target group

- Can be implemented by the team

- Not a project, feature, etc.

Following questions can help to identify the most relevant objectives:

- “Why is this important / more important?”

- “Why is it important now?”

- “Does the idea pay into the (product) vision and (product) strategy?”

- “If work is done on the 1-3 Objectives, what other issues would need to be stopped/delayed to achieve this?”

These questions not only help to limit the number of OKRs, but also enable a valuable conversation that creates situational awareness.

It is advised to define ambitious objectives so that the participants can challenge their limits and also try out unconventional ideas so that creative and innovative solution ideas can emerge. Whether an objective is ambitious enough should be the decision of the team itself.

Objective Examples

- We create awareness about DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) in companies.

- Our customers love the simplified checkout process.

- Visitors can find and buy within a minute.

Important: Objective is not a new term for a project. It describes a change and value to be provided for a specific target group.

3.3. Key Result

Key Results are quantitative descriptions that make progress towards the Objective measurable. Each Key Result covers a different perspective of the objective so that there is a balance between different aspects.

Key Results Checklist

- Measurable outcome

- Ambitious but realistic

- No dependencies between key results

- Continuously measurable

- Can be implemented by the team autonomously

- Not a lagging KPI, feature, binary milestone, to-dos, etc.

A Key Result should typically answer the following question: “How can we measurably observe whether or to what extent the objective is achieved?”

Key Result Examples

- Usage on mobile devices increased by 50%

- 60% of the customers uses the new service

- 20% of the staff participates in the information event

The following five criteria help to define good key results.

3.3.1. Outcome oriented

Although Key Results were originally the measurable steps to achieve the objective, an outcome-oriented way of thinking is now becoming established. According to this, a Key Result should not measure productivity or performance, but the effect of the deliverables. Following two terms clarify the difference between productivity and effect:

- Output: The deliverable, that is crated, shipped, produced.

- Outcome: The effect, resonance or change in behaviour that is created through deliverables.

“Outcome is a change in human behaviour that drives business results.”

Joshua Seiden, Outcomes over Output

Although what is delivered or produced is a concrete result (output), the use of the products is not always assured. Therefore, it is problematic to control the output alone by telling a team what to do. Rather, the focus should be on the expected added value or effect of the output. Thus, when a team is asked to create or change a certain effect or behaviour of customers, it enables the team to work more freely on adequate solutions that deliver this desired added value.

Tip: With outcome-oriented Key Results, the team focuses more on the effect of their work rather than just the number or speed of implementation of the delivered features. For example, while an output-oriented Key Result such as “write 5 blog posts” only measures productivity, an outcome-oriented Key Result such as “each blog post was shared 100 times” would rather focus on the effect or resonance generated with the readership.

Although what is delivered or produced is a concrete result (output), the use of the products is not always assured. Therefore, it is problematic to control the output alone by telling a team what to do. Rather, the focus should be on the expected added value or effect of the output.

Tweet

3.3.2. Measure to learn

It should be avoided that the metrics in Key Results become that target itself. In other words, it is not the achievement of a metric that is the goal, but what these metrics tell about the effect of the work.

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Goodhart’s law

Just as Goodhart’s Law describes, when a Key Result becomes the target, it loses its power, because the focus is then not on the actual learnings but on achieving the goal at any cost (hacking the system).

Rather, Key Results are meant to help navigate complex contexts to gain certainty by having metrics validate working hypotheses and indicate what kind of work works well and what resonates with the respective target group. A Key Result that is not achieved can therefore be just as valuable as one that is achieved, if it provides new insights into products, customers or the environment we play in.

3.3.3. Influenceable by the team

In order for a team to measure, reflect and adjust the outcome of their work – which is the core idea of working with OKR to navigate complex contexts – teams should be able to influence their Key Results themselves.

After all, if weeks or even months have been spent working on a solution or hypothesis, but the team cannot see the results directly, the team does not know whether and to what extent their work has a positive or negative impact on the outcome. This means that they have no opportunity to learn because they cannot reflect on cause and effect. Moreover, there is probably nothing more frustrating than not being able to see or measure the impact of one’s own work.

3.3.4. Continuously measurable

When Key Results are used for learning, the impact of the work should be measured in a timely manner so that it can be validated what is working well, what is not working well, what should be done more or less of, and when it is the right time to pivot. If a team spends 3-4 months working on ideas whose impact they can only see at the end of an OKR cycle or even later, it means that the team has spent 3-4 months on something without knowing whether it has really created added value.

To counteract this, the concept of Lead & Lag Measures from the book “The 4 Disciplines of Execution” by the authors Sean Covey, Chris McChesney, Jim Huling, and Andreas Maron helps.

| Lead Measures | Lag Measures | |

| Time | Predict whether and to what extent a goal will be achieved. | Show whether a goal has been reached. |

| Predictability | Drive progress and increase the likelihood of achieving a goal. | Demonstrate the success of past achievements. |

| Influenceable | Are directly influenced by the team. | Are influenced by various factors. |

| Actionability | Are dynamically adaptable. | Can no longer be influenced. |

Lead measures that are continuously measured and can increase the likelihood or predictability of achieving desired goals help to make timely data-driven decisions. For this reason, lead measures should rather be used when defining OKRs to enable fast and continuous learning.

3.3.5. No impact oriented lagging KPIs

The concept of lead and lag measures also helps to understand that financial business KPIs such as EBITDA, sales, market share, etc. are not well suited as key results because a) they measure the results of past performance at the time of measurement and b) they are too abstract and out of a team’s sphere of influence. Joshua Seiden explains in his book “Outcomes over Output”, this type of business objective with the term Impact, and emphasises that the outcomes should be selected in such a way that they positively influence the (business) impact as much as possible.

Example of the relationship between output, outcome and impact:

5x blogposts per month (output) may help to increase the number of website visits by 20% (outcome) and thus possibly increase the number of customer enquiries and sales (impact) by 10%.

Read more: Types of Metrics and how to use them in OKR context?

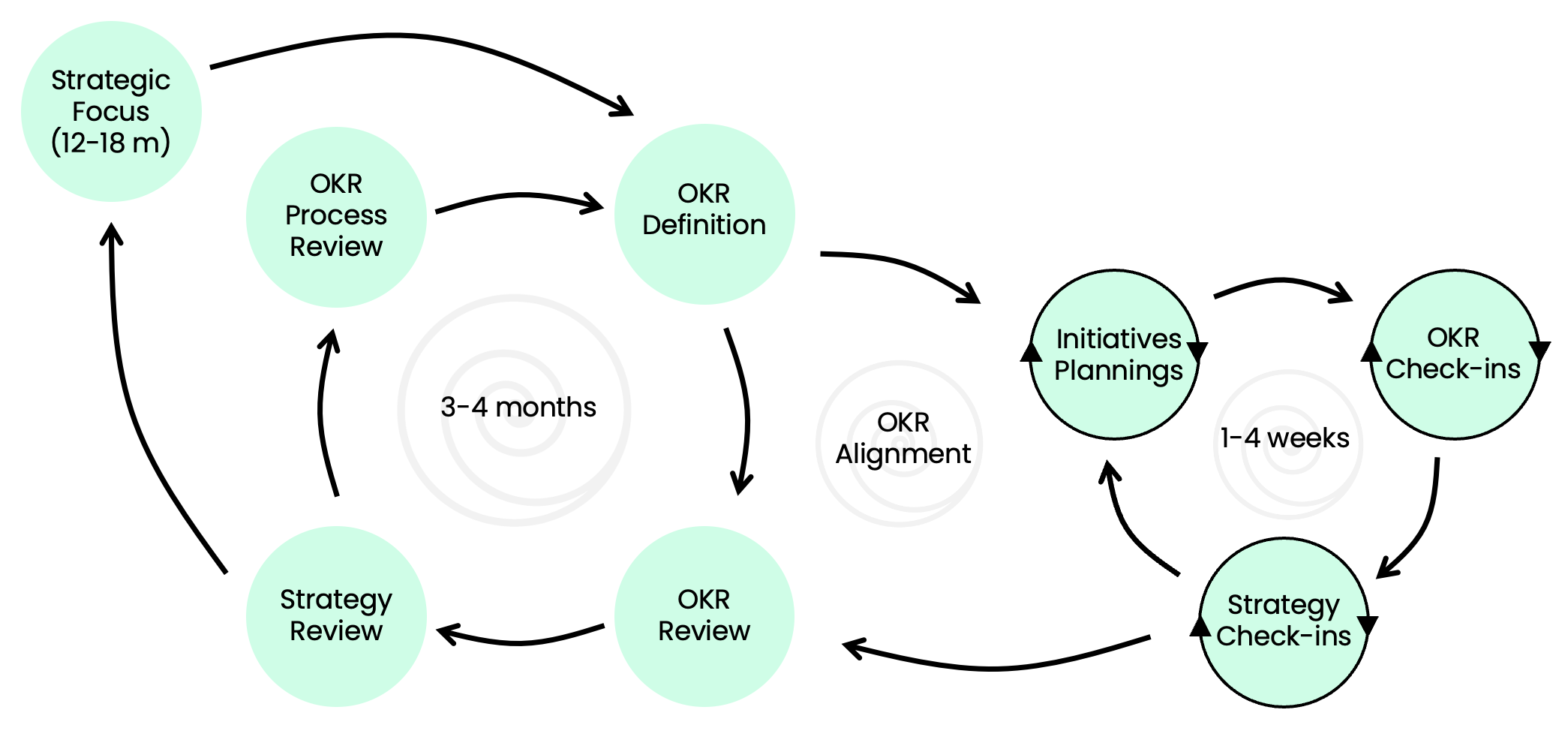

4. OKR Cycle

Defining good OKR sets is not enough; they must also be implemented. In order to work on OKR sets and discuss progress, appropriate routines need to be agreed upon.

The visualised OKR cycle serves as an aid to facilitate regular conversation between teams and leadership and can be adapted according to context and environment.

Defining good OKR sets is not enough; they must also be implemented. In order to work on OKR sets and discuss progress, appropriate routines need to be agreed upon.

Tweet

4.1. OKR Definition

OKR Cycle starts with setting OKRs. After the management/leadership has defined the vision and the mid-term strategy for the next 12-18 months, the teams can define their OKR sets for the next 3-4 months.

The central question of the OKR Definition Workshop is: “What do we, as a team, want to achieve in the next OKR cycle to make an impact-oriented and visible contribution to mid-term strategy?”

For productive OKR Definition Workshops, it is essential that team members come prepared. Ideally, teams collect information about problems or needs of their target group and illustrate these for all team members by means of customer journeys, touchpoint descriptions etc.

In the OKR Definition Workshop, which usually lasts 3-4 hours, team members can share their observations and analyses, discuss possible strategies and tactics and decide what to focus on next.

At the beginning of the workshop, all possible ideas should be collected uncensored (divergence), which are then grouped and categorised in an active exchange to highlight similar ideas or tendencies (convergence). Through joint discussion, the team selects the 1-3 most important objectives and then defines the matching key results.

The active participation of all team members in OKR Definition Workshop is very important, as each person’s perspectives bring a valuable input to the discussion and the conversation around the “outcome” to be achieved often serves as an eye opener.

Tip: Good facilitation and moderation play a major role to run all workshops and should therefore not be underestimated. For this reason, all “events” (workshops, reviews, check-ins), in the OKR cycle should be accompanied by a person who ensures good facilitation and moderation and also helps with their OKR expertise. Depending on the organisation, this role is called OKR Master, OKR Champion, OKR Ambassador, OKR Shepard or OKR Agent (see section 7.3).

The active participation of all team members in OKR Definition Workshop is very important, as each person’s perspectives bring a valuable input to the discussion and the conversation around the “outcome” to be achieved often serves as an eye opener.

Tweet

4.2. OKR Alignment

The goal of the OKR Alignment Workshop are versatile: On the one hand, it serves to build a common understanding of the strategy and to select focus topics for the next OKR cycle. In addition, in scaled environments, for example when several teams are working on the same topic, an OKR alignment helps to identify dependencies, synergies or duplications.

If teams find that they are working on similar strategic issues and/or tactics, they could hold an alignment workshop to link their OKR sets and, if necessary, define a common OKR set.

Ideally, all teams that work together on a product, including infrastructure, marketing, sales, etc., take part in this OKR alignment workshop. Because creating a common understanding of the strategy and tactics helps everyone involved. The findings from the OKR Alignment Workshop can be used to streamline the OKR system, possibly also the organisational structures as a whole.

Formats like Open Space or Marketplace work wonderfully for OKR Alignment Workshops: First, each team briefly presents their OKR sets to all participants. Meanwhile, the listeners take notes (dependencies, synergies, duplications) on anything they would like to discuss later in this regard. Afterwards, the rooms can be opened for breakout sessions where the team representatives can visit each other to give/take feedback, share ideas on how the identified dependencies could be solved or how they could support each other in implementing their OKR sets. After these breakout sessions, everyone comes back together, all teams present their key findings and share what adjustments they will make to their OKR sets.

The duration of an OKR Alignment Workshop varies greatly depending on the number of teams and participants. For 5-10 teams, the workshop can last 2-4 hours, while for 10-20 teams it can last a whole day, and for over 20 teams it can last two 2 days.

After the OKR Alignment Workshop, in the next week or two, the teams should address the agreements made with the other teams, make necessary adjustments, and finalise the OKR sets so that the next OKR cycle can officially start.

4.3. Initiatives Planning

Initiatives are ideas or experiments that can be implemented within 1-4 weeks in order to get quick feedback on their effect on the target group. The results of implemented initiatives should feed into the Key Results.

Initiative planning is a key event in which each team plans the actions and activities for the actual implementation of its OKR sets. These meetings are crucial to prevent the phenomenon of “set and forget”.

How exactly this meeting is structured depends on the team context. It is important that it becomes part of the team’s daily work routine. If team meetings are already taking place, they can be extended to include initiatives planning.

Experience shows that the initial initiative planning, i.e. the first meeting after OKR Definition Workshop, takes about 2 hours. After that, the team should meet regularly (e.g. 1-2 weeks) so that the initiatives can be continuously adapted or new ones defined depending on interim results. The tasks for implementing the initiatives must be clearly distributed within the team so that everyone knows at all times what is currently being worked on.

Tip: If the team works with Scrum, it is possible to link the two frameworks. To do this, the artefact “product goal” can be formulated as an OKR set and derive backlog items accordingly. The initiatives (epics, features, user stories, etc.) defined in the sprint planning for the realisation of the OKR sets are then implemented in the sprints.

4.4. OKR Check-ins

The central question in an OKR check-in is: “What progress do we see in the Key Results through the implemented initiatives and what does this say about our next steps?”. OKR check-ins bring together the involved people to share insights how effective the initiatives are/were.

This meeting, like the initiatives planning, takes place regularly (at least every 2 weeks) and should be kept as short as possible (15-30 minutes). For the meeting to be effective, it must be well structured and needs good facilitation.

The following three questions can provide a good structure for OKR check-ins:

1. Progress: What progress have we made?

Teams should submit the current status of the key results in any tool agreed by the team (Excel, Miro, Jira, Wiki, etc.), before the check-in, so that the changes can be seen directly in the meeting and the exchange on the content can start immediately. Each team can define their own type of scoring.

Scoring

- 🔴 0-30%: The initiatives are not moving us forward. We should pivot.

- 🟡 30-70%: We are making progress but should rethink the initiatives a bit.

- 🟢 70%-100%: The initiatives are moving us forward well. We can do more of them.

2. Confidence: How confident are we?

It is possible that the figures do not tell us the whole truth. A Key Result where no progress can be seen does not automatically mean that the team is not working on it. It may take 2-4 weeks before the effect can be measurably observed. In the same way, even good progress can be misguiding, if an unforeseen obstacle arises that will negatively affect all further activities. For these cases, the question of “confidence” is a good complement for an effective exchange.

Confidence Level

- 🤩 We’ll make it

- 😰 Could be better! We should re-think our initiatives!

- 😩 Won’t make it, unless…

3. Reflection: What have we learned so far?

An OKR check-in should also serve as a reflection by sharing key findings.

Useful questions include:

- Which hypotheses have been validated so far?

- What worked particularly well?

- What did not work?

- What is holding us back?

Finally, new initiatives, to-dos, action items can be noted down and addressed.

Tip: If a team is working with Scrum, the Sprint Review is a good opportunity to integrate the OKR check-ins. After all, the goal of a Sprint Review is to discuss “progress toward the product goal.” (Ken Schwaber & Jeff Sutherland, The Scrum Guide 2020)

Read more: How to combine OKR with Scrum?

4.5. Strategy Check-ins

In larger organisations it is also advisable to conduct strategy check-ins regularly (at least every four weeks). These are structured similarly to OKR check-ins. The main difference is the group of participants. The team representatives and the managers come together to discuss the current progress, findings and obstacles that are becoming apparent in the pursuit of the OKR Sets.

The effect of the OKR Sets on business impact is also reviewed. The aim is to identify potential problems, opportunities or trends at an early stage and to incorporate them into the strategy accordingly, as well as to consider any necessary course changes.

4.6. OKR Review

At the end of an OKR cycle, each team reflects on its results and working methods. In this session, the focus is on the principle of Inspect & Adapt. The entire team that was involved in the implementation of the OKR sets participates in this session.

The OKR Review is organised in two parts.

Part 1: Review

The aim of the review is for the team to share whether and to what extent they have achieved their OKR Sets and what they have learned from them. The focus is on the validation of the work and its effects.

In the OKR check-ins, the progress of the key results was regularly discussed, but what does that say about the achievement of the objectives?

A mistake that often happens at this point is the assumption that the achievement of an Objective can be mathematically calculated by the average of the Key Results achievement score. However, in a complex world, the relationships are not linear. For this reason, each team should take time in the OKR review to evaluate whether or to what extent they have achieved the Objectives.

If the team feels that the objective has not or not fully been achieved, the team should discuss the following options:

- Keep it: We need to continue to work towards achieving the objective. But then…

- Change it: The objective has to be adapted according to new insights.

- Drop it: The objective was not achieved and is no longer relevant.

Tip: Be careful with the “Keep it” option, as there is a high risk that the objective is an “evergreen” and is therefore inherited from one OKR cycle to the next. In such cases, it makes sense to create focus and to specify which change should become visible in 3-4 months.

The OKR Review is not only used to assess the achievement of the OKR sets, but also to make explicit what has been learned.

The following questions enable the team to have a qualitative exchange:

- Which hypotheses were validated or not validated?

- To what extent did we contribute to the implementation of the strategy?

- What have we learned about the behaviour of the customers?

- What new insights have we gained about the market?

- Which of these insights are important for the further development of the strategy?

If a North Star Metric (see section 3.1) has been captured in the strategy, at latest now is a good time to review the impact of the OKR sets on this metric.

Part 2: Retrospective

Working with OKR is a change for everyone and especially in the first OKR cycles, teams realise that they need to adapt their ways of working. The OKR retrospective opens the space to reflect on what is going well, what is not, and what needs to be adjusted so that the team can work better and more effectively together in the future, which in turn will create a positive effect on the quality of the OKR sets.

So while the review is about the achievement of the OKR sets, the retrospective looks at the collaboration of the product team.

The central question is: “How do we want to (better) shape our cooperation in the future?”

In addition, valuable insights can be gained in the retrospectives with individual teams, which provide information for optimising the entire OKR process.

Retrospectives can be structured by asking the following questions (Esther Derby, Diana Larsen: Agile Retrospectives):

- Gather Data: Review objective and subjective information to create a shared picture. Bring in each person’s perspective.

- Generate insights: Step back and look at the picture the team created.

- Decide what to do: Prioritize the team’s insights and choose a few improvements or experiments that will make a difference for the team.

Tip: If the team does regular retrospectives anyway, it is recommended to add an OKR retrospective to the scheduled retrospective at the end of each OKR cycle.

4.7. Strategie Review

Based on the insights gathered during an OKR cycle, the strategy can be reviewed, validated and adapted as needed. This allows the organisation to continuously adapt according to current market events, enabling true business agility.

Similar to strategy check-ins, the strategy review involves the team representatives and leaders to discuss findings from the team’s OKR reviews at the end of each OKR cycle.

At this meeting, the North Star Metrics and Business KPIs (business impact) are also reviewed to derive next strategic actions from.

The conversation can be structured with the following questions:

- What are the most important insights regarding customer behaviour (problems, needs, trends)?

- What major market changes (disruptions, competition, economy, politics, society) have we observed that could influence us?

- To what extent do the changes play a role in our strategy?

- What could create competitive advantages for us?

The strategic insights and decisions from the strategy review serve as an important basis for the upcoming OKR definition workshops to start the next OKR cycle.

4.8. OKR Process Review

Working with OKR changes communication and structures within a team, between teams, and thus in the whole organisation. There focus shifts to outcomes, strategy development becomes part of everyone’s work day, teams collaborate with each other in a different way, the work of teams is structured differently, mindsets shift from planning ready-made solution to validating hypotheses, and much more. All of this is driving a cultural change in the company. This is a highly complex matter that should be continuously reviewed, validated and adapted.

This is exactly the goal of an OKR Process Review. In the middle or at the latest at the end of each OKR cycle, those responsible for the OKR implementation (e.g. the OKR Integration Team – see section 5.1.) should meet and discuss the findings from team’s retrospectives, in order to derive possible changes for the next cycles.

The aim is to find out how the OKR framework helps to create alignment and focus, and how to take the work with OKR to the next level so that it becomes more and more internalised and institutionalised.

The following questions will help to structure the session:

- What works well?

- Where do we need to adjust?

- Do we miss certain checkpoints or communication channels?

- Where can we streamline?

- Are new OKR topics or teams being added?

- How can we make the work with OKR visible and tangible throughout the organisation?

In order to check and validate whether and to what extent the work with the OKR framework helps, it needs to be clear which problems are to be solved with an OKR implementation. It is advisable to deal with this question at the beginning of an OKR implementation. Setting OKR for the OKR implementation itself makes these reviews even more powerful.

In order to check and validate whether and to what extent the work with the OKR framework helps, it needs to be clear which problems are to be solved with an OKR implementation.

Tweet

5. OKR Implementation

The idea of OKR seems simple, but the implementation is definitely more complex than it appears. Every implementation is different because every organisation is different and has different needs. For this reason, there is no “one size fits all” solution. Nevertheless, the following will provide some guidance on typical phases of an OKR implementation and what to look out for.

5.1. The first steps

Since working with the OKR framework drives a complex cultural change, the principle of “Probe Sense Respond” also applies to OKR implementation – as it does to all other complex challenges.

According to this, true to the motto “Nail it, before you scale it”, it is recommended to introduce the OKR Framework not for an entire company right away, but iteratively, so that the potential (and very probable) beginner problems do not arise in the entire organisation, but OKR can be rehearsed and learned in a small environment.

The beginning of an OKR implementation is critical for later success and should therefore be planned carefully.

The following four points will help to structure the first steps well.

5.1.1. Ask the question “Why OKR?

The first question that should be asked before any OKR introduction is why the framework should be introduced or what problems it should solve. Here, as for all complex challenges, it is advisable to define the vision and mid-term-term goal of OKR introduction and then define OKR sets every 3-4 months, implement them, review them regularly, validate them and adjust them if necessary.

5.1.2. Form an OKR Integration Team

Ideally, an interdisciplinary OKR Integration Team will be formed to deal with the introduction and further development of the OKR Framework in an organisation in the long term.

Members from the People & Culture Team, Organisational Development, Management and Product Teams could be part of this team, so that they can view the (further) development from different perspectives and meet regularly to review the OKR process.

5.1.3. Find a good starting point

Since the first OKR cycles are primarily about learning how to work with OKR, it is advisable to start by finding teams, areas or themes that are well suited to working with OKR.

The following factors help in the selection process:

- As broad and deep as possible: Find a topic for which vertical (different organisational levels) and horizontal (neighbouring teams or areas) alignment is necessary so that the new type of collaboration can be tested as effectively as possible.

- Not too complex but not too simple: Find topics that are complex so that the work with OKR makes sense at all, but at the same time is not influenced by too many unknown factors. But the topics should not be too simple either. After all, it should be made tangible how the OKR framework can help.

- Create visible impact: The selected topics should be as interesting as possible for all employees so that curiosity and interest in OKR can be generated indirectly and the results can be experienced by all.

5.1.4. Starting with volunteers

In every organisation there are early adopters, i.e. people or teams who like to be the first to try out new frameworks, tools, etc. and enjoy helping to shape change.

For the beginning of the OKR implementation, it is advisable to start with these people or teams in order to learn together with them how the OKR framework can work best in the respective organisational context. They can be ambassadors of change as the OKR roll-out progresses.

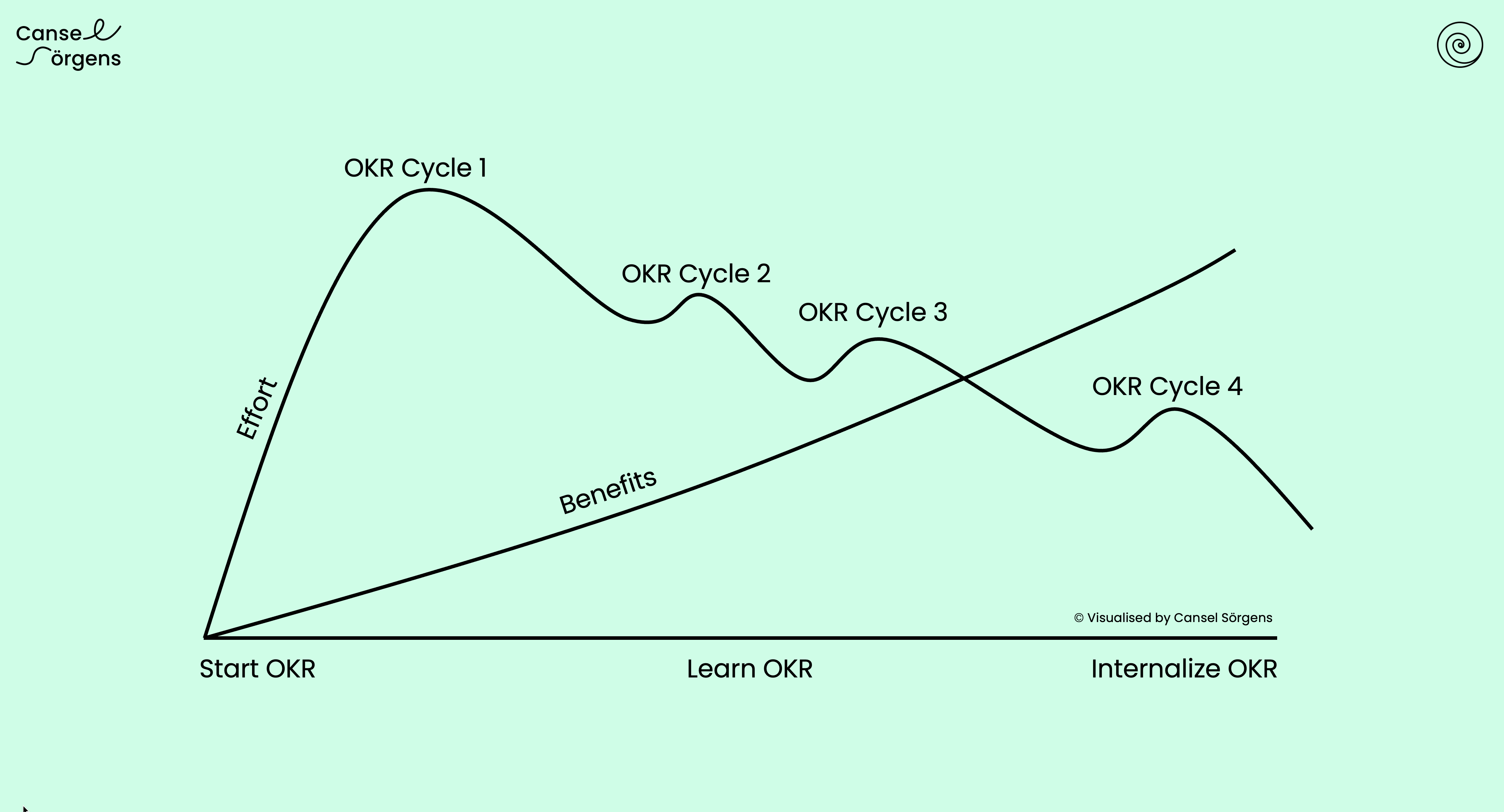

5.2. The first OKR cycles

The effort required to get the OKR Framework rolling in an organisation is high at the beginning and the benefits are not immediately apparent. However the first 1-3 OKR cycles make it or break it.

It usually takes at least 3 to 4 OKR cycles to learn and internalise the “OKR language” and logic. Once this phase has been achieved, the institutionalisation phase begins, which usually takes another 3 to 4 cycles until OKR is an integral part of an organisation’s everyday life.

Implementing OKR requires perseverance.

𝟬-𝟭 𝗢𝗞𝗥 𝗰𝘆𝗰𝗹𝗲: The first steps take time and require care and attention.

𝟮-𝟯 𝗢𝗞𝗥 𝗰𝘆𝗰𝗹𝗲𝘀: You’ll start to understand the nuances, e.g. output & outcome, lagging & leading, etc.

𝟰+ 𝗢𝗞𝗥 𝗰𝘆𝗰𝗹𝗲𝘀: You’ll start finding your own best practices that fit your context.

Read more: OKR implementation program “𝗖𝗿𝗮𝘄𝗹 – 𝗪𝗮𝗹𝗸 – 𝗥𝘂𝗻”

Tip: Working with an external OKR expert at the beginning of an OKR implementation saves a lot of time and trouble by helping them to avoid the typical pitfalls. When choosing an external OKR expert, it is important to make sure that the consultant has accompanied several OKR implementations in different contexts.

5.3. Building in-house OKR know-how

The more areas and teams adapt the OKR framework, the more support it needs. Since the use of external OKR coaches cannot be scaled sustainably, it makes sense to start building up internal knowledge early enough.

To this end, external OKR experts can train internal OKR agents and accompany them through coach-the-coach programmes for a certain period of time until a certain level of maturity is reached, so that the internal OKR agents can eventually take over the monitoring of the OKR process completely on their own.

In addition, long-term cooperation with external OKR coaches can enable continuous supervision of the internal OKR agents as well as sustainable know-how development.

6. OKR Structure

OKR structure refers to the organisational levels and team structures. These are in fact very diverse and should be taken into account when introducing OKR. The reasons for introducing OKR, the challenges to be solved and the current structures of the organisation play a major role in defining the OKR structure.

One of the most common mistakes in OKR implementations is that the organisation chart is adopted one-to-one when defining the OKR structure. This means that each team displayed in the organisation chart is expected to define OKR sets. However, since most organisational charts do not reflect the actual communication channels for value creation, the usual dependencies between teams will continue to exist in the new OKR process. If teams cannot implement their OKR sets without input or support from other teams, this not only increases the coordination effort, but also the frustration of the team members, as they spend more time coordinating than realising their OKR sets, and the promised benefit of effective work is not fulfilled.

Instead, the introduction of OKR offers an opportunity to take into account the actual collaboration between teams and areas and to set up “OKR teams” in a way that the teams really create value together. An OKR structure should enable dynamic collaboration in networks.

Read more: Don’t cascade OKR! Create cross-divisional collaboration with dynamic networks!

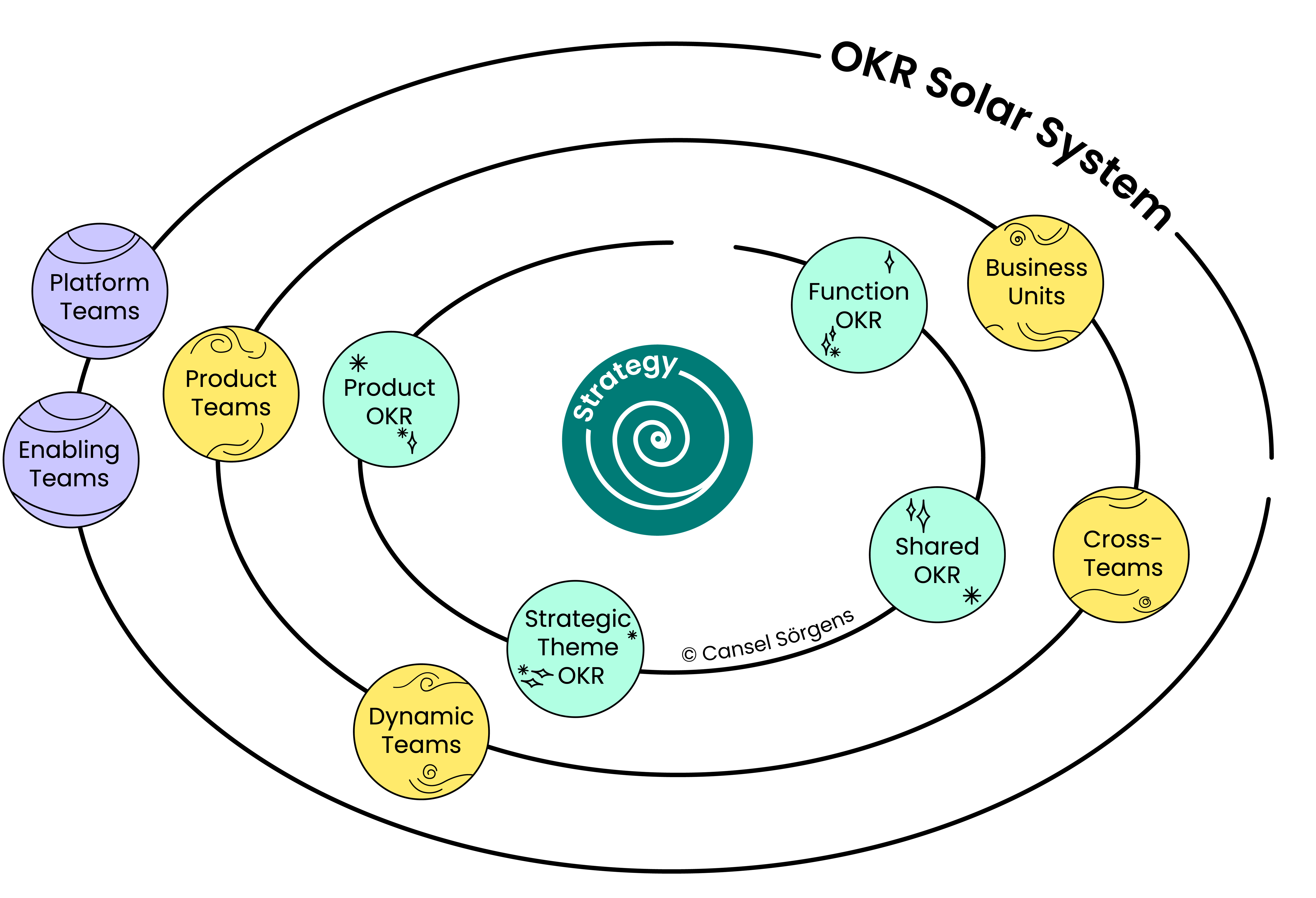

6.1. OKR Solar System instead of strict cascading

Although for decades the understanding has been that OKR sets must cascade from top to bottom in order to establish alignment, time and again this approach proves to be impractical in reality.

A cascading OKR structure has the following disadvantages:

- In a cascading OKR structure, where the lower organisational level has to take over the OKR from the level above, the people are left with too little room for manoeuvre. This kind of cascading OKR structure limits any creativity and autonomy.

- A change in one OKR triggers a chain of reactions, so all related OKR sets have to be adjusted as well.

- Teams have to wait until all higher levels have defined their OKR sets, slowing down the whole process.

- The larger the organisation, the higher the effort until all have defined their OKR Sets and aligned with other teams and areas. This causes a lot of time spent in OKR workshops and coordination meetings, which is certainly not in the spirit of any OKR implementation.

OKR should actually create a link between the vision, strategy and implementation so that those involved can make decisions in their day-to-day work in a way that is as self-organised as possible. However, a cascading OKR architecture is not the solution. Rather, it needs a tangible and directional strategic goal around which teams can organise themselves (see section 3.1). Through the Vision and mid-term strategic focus, the OKR structure can be built like a “solar system“.

As shown in the figure, the mid-term strategic focus represents the sun and the individual OKR teams are the planets. Due to the Sun’s gravitational pull, the planets remain bound to it; nevertheless, each planet also revolves around itself and has its own rhythm. In addition, some planets also have their own satellites orbiting them.

The Mid-Term Strategic Goal represents the sun and the individual OKR teams are the planets. Due to the Sun’s gravitational pull, the planets remain bound to it; nevertheless, each planet also revolves around itself and has its own rhythm. In addition, some planets also have their own satellites orbiting them.

Tweet

6.2. Types of OKR Teams

As organisations are very diverse, this should also reflect their OKR architecture. Three types of OKR teams that are often seen in product organisations are explained below.

6.2.1. Product OKR

In a product-led organisation, it makes sense to first define the product vision and the mid-term strategic product goal. Then the OKR sets can be derived from it. There are two options for this, which can be chosen depending on the context and size of the organisation.

The first option is that the team members, who can contribute to the development and implementation of the product strategy with their insights, knowledge and experience, define OKR sets for the main product every 3-4 months. Then the sub-product teams (teams working together on the same product) and enabler teams (teams working on core services, such as IT infrastructure) plan their activities, initiatives, actions, etc. based on these Product OKR sets.

The second option is that the sub-product teams each define their own OKR sets linked to the product vision and strategy. This variant only works well if the sub-product teams can work as autonomously and independently of each other as possible.

Ultimately, opportunities should always be sought that enable lean structures and effective collaboration. The decision is up to the product teams themselves, because they know their working context best and can assess which variant is more suitable for them.

6.2.2. Shared OKR

Areas such as Marketing can work independently on their own OKR sets (e.g. conclude new marketing partnerships), but the strategy for the introduction of a new product must be developed and implemented in collaboration with the product teams. In such cases, it is recommended that the divisions jointly define so-called Shared OKR (introduced by Felipe Castro). Then each team derives its respective initiatives and tasks accordingly.

One team may be responsible for a specific key result alone. In other cases, two teams are jointly responsible for a Key Result, or no team is solely responsible for a Key Result, but each team defines its initiatives to show how they will contribute to achieving the Shared OKR.

The teams, or the representatives of the respective teams, should meet regularly (at least every two weeks) for OKR check-ins to synchronise and discuss next steps. At first, this sounds like additional meetings. However, this is not the case, as the teams would usually have met anyway to synchronise.

Through OKR, however, the impact of the work of all the teams together is more focused and a sense of “we” is created or reinforced by shared goals, so that a true collaborative culture can emerge.

6.2.3. Strategic Theme OKR

In every organisation there are always topics for which there are no dedicated teams (yet). Strategic topics, cultural changes, new business, etc. are typical examples.

By announcing and informing everyone about the current strategic themes, interested employees can be invited to work together on such topics in cross-level and cross-departmental, dynamic and temporary teams.

After each OKR cycle, employees can decide whether or how to continue working on the theme, whether to invite new members, and how to move the results from the previous cycle into the organisation. This could mean that at some point a dedicated team will be created.

Read more: Cross-divisional collaboration with Strategic Theme OKR

Tip: Newly formed “collaboration teams” should agree on their work routines, because the additional effort should not be underestimated. However, this does not arise because the teams structure their work with OKR, but because the teams participate in parts of the strategy for which dedicated teams or capacities have not yet been defined.

Avoid individual OKR: OKR promotes a collaborative, participatory and cross-cutting way of working because it often requires the participation of multiple parties to create end-to-end value. In complex subject areas, it is hardly conceivable that one person alone can generate end-to-end value. However, this does not mean that individuals cannot contribute anything of value. On the contrary, the defined OKRs are worth nothing if they are not worked on by individuals. The skills of each team member are needed for implementation. All those involved are therefore called upon to derive their work from the next relevant OKR sets. Moreover, if individuals had their own OKRs, these would be prioritised higher in case of conflicts. And this tends to hinder a collaborative culture.

7. OKR Roles

Working with OKR needs to be supported by different roles. Only the interaction of all of them ensures effective OKR. The central roles and their tasks in the OKR process are outlined below.

7.1. Leaders

Leadership makes it or breaks it. Without the commitment of leaders, an OKR implementation will quickly reach its limits, because strategic alignment needs leadership that paints a picture of the future that inspires participation. Through a clear strategy and shared goals, leaders enable autonomy, so that teams can work in a self-organised way in the given context.

Leaders have several opportunities in the OKR process to communicate more effectively with their teams. For example, in OKR Definition Workshops, they can explain to teams the background and context for the selected strategy and involve teams more in the strategy development process.

In addition, in OKR check-ins or strategy check-ins, for example, managers can identify possible obstacles at an early stage and support the teams in removing them as quickly as possible.

Furthermore, in regular feedback sessions with individual team members, they can discuss their professional and personal development path and see which individual skills would be helpful to the realisation of the strategy and OKR.

Finally, the way leaders engage in the OKR process not only plays a major role in the success of the process, but also in the sustainable establishment and development of a business model.

Through a clear strategy and shared goals, leaders enable autonomy, so that teams can work in a self-organised way in the given context.

Tweet

7.2. Team Members

Working with OKR can promote structures in which strategy development and implementation are no longer seen as a task of top management alone. Critical strategic thinking can become part of the day-to-day work of every employee.

A clear strategy and continuous exchange during OKR cycles give everyone a “structured flexibility”. Teams can be more self-organised in their day-to-day work in the given context, making informed decisions about what to work on, how and when to contribute to the strategic goal and OKR sets. They see and are seen how to contribute to the bigger picture and experience the effectiveness of cross-team collaborative working.

Structured flexibility needs committed teams that take responsibility for their decisions and work. Effective OKR needs team members who use their expertise to identify and implement solution ideas for the needs of their target group. This means, on the one hand, that teams need to know their target group well and be in regular contact with them, and on the other hand, that they regularly check whether and to what extent the solutions they choose influence the strategy and business impact.

By working with OKR, team members become active shapers of the company’s success, which require them to broaden their skills to think and work in a more customer-centric, strategic and business-focused way.

7.3. Internal OKR Agents

Effective work with OKR requires OKR expertise on the one hand and well-structured and facilitated workshops and meetings on the other. OKR Agents can support teams with their OKR know-how and provide a collaborative and trusting environment with good facilitation and moderation skills.

As described in section 5.3., external OKR coaches can train interested employees to become OKR Agents and accompany them for a while, so that they can later take over and continue to accompany the OKR process on their own.

OKR Agents support teams during the OKR cycle in their OKR workshops and meetings and ensure that the “new” rituals and ways of thinking become a habit.

However, they are not responsible for the quality of the defined OKR sets in terms of content, but accompany teams as coach to leverage knowledge and help the teams to formulate their ideas as good OKR sets. OKR Agents should therefore not support their own teams, as they need to remain impartial when moderating these workshops.

The internal OKR Agents could form a Community of Practice to strengthen each other, develop ideas and work out how to make the use of OKR even more effective.

Tip: Agile Coaches, Scrum Masters or Team Coaches are very well suited for the role of OKR Agent because of their skills, if they broaden their knowledge with OKR know-how.

7.4. OKR Process Owner

OKR Process Owner drives sustainable OKR implementation and ensures continuous communication so that everyone understands why the OKR framework is being used. In collaboration with managers, teams, OKR Agents and external OKR coaches, the OKR system should be continuously reviewed and adjusted as necessary.

Organisation Development Managers are particularly suited to this role, as the implementation of an OKR framework has an impact on many neighbouring organisational structures and these need to be considered holistically rather than locally.

7.5. External OKR Experts

OKR implementations that are not effective or do not solve existing problems, possibly make it even worse, have one thing in common: they were usually started without the support of experts with long standing practice proven OKR know how.

The complexity of an OKR implementation is often underestimated and after 2-3 days of OKR training, employees start to implement the OKR framework in their organisation. Or OKR consultants with not enough practical experience get engaged, who read a book or two. After 1-2 years, either the attempt is stopped or other external OKR coaches are invited to straighten out the OKR process.

In this first 1-2 years so much can go wrong, so that a correction afterwards costs more time and energy, to unlearn and re-shape it. For this reason, it is advisable to work with experienced OKR coaches right at the beginning of an OKR implementation, to lay the foundation.

Check my OKR implementation program “Crawl-Walk-Run”™.

8. OKR Principles

While many decision-makers can be quickly convinced of the benefits of OKR, the necessary conditions and principles are often not considered. In order to unleash the power of OKR, habits and beliefs must be challenged, which requires a genuine willingness to change.

In the following, three working principles are described that are indispensable for successful work with OKR.

8.1. Find the right balance between top-down and bottom-up

While the leadership communicates an inspiring vision and an activating and directional strategy and provides a clear Mid-Term Goal as orientation, the teams develop matching tactics and solution ideas and decide for themselves what they will implement when and how.

However, if goals are only defined top down, the motivation of the employees will suffer, because people identify primarily with things they have set for themselves. If, on the other hand, goals are only defined bottom up, there is a high risk that the individual teams will not take the “big picture” into account, but only optimise locally.

There is no generally applicable formula for the right balance between top down and bottom up, such as 40% top down and 60% bottom up. Rather, it is achieved through a participatory OKR process in which managers and teams collaborate and continuously exchange ideas at the strategic and tactical levels.

If goals are only defined top down, the motivation of the employees will suffer, because people identify primarily with things they have set for themselves. If, on the other hand, goals are only defined bottom up, there is a high risk that the individual teams will not take the “big picture” into account, but only optimise locally.

Tweet

8.2. Disconnect OKR and Performance Management

If working with OKR is to foster ambitious goals, creativity and innovation, it needs an environment of psychological safety where people do not have to be afraid to share their ideas and engage in experiments even if they might fail. So it needs a culture where errors are understood as part of the process.

But if teams are judged on OKR results, if OKR is used for employee evaluations, monetary incentives, etc., people will only define OKR sets that they are confident they can achieve. This means that the comfort zone will not be left or a transition into the learning zone, where innovative ideas can emerge in the first place, will not take place.

For this reason, OKR should in no way be linked to performance management or similar systems. Instead, a culture of continuous and frequent feedback should be established, replacing the annual or bi-annual, often one-sided employee reviews.

Instead of filling out standardised forms, team members and leaders can engage in conversations about how team members can (more) effectively engage and how managers can support them in doing so.

If working with OKR is to foster ambitious goals, creativity and innovation, it needs an environment of psychological safety where people do not have to be afraid to share their ideas and engage in experiments even if they might fail. So it needs a culture where errors are understood as part of the process.

Tweet

Read more: How to connect Performance Management and OKR?

8.3. OKR not for everything

Some teams tend to formulate everything they do as OKR. This phenomenon can be observed when the work with OKRs has been communicated as the most important thing in an organisation. If it is suggested that those who have no or few OKRs are not working on anything important, OKRs are going to be used inflationary for everything.

To counteract this, two types of work must be made clear:

- Business as Usual (BAU): The work for stability today (keep the lights on)

- Strategic work: Working for competitiveness tomorrow (turn the lights on)

Both types of work are equally important, but require different approaches.

While it is understandable that everyone in an organisation should use the same framework to have a consistent approach, it is time to accept the complex reality of the 21st century that there is no one right answer (methods, frameworks, tools, etc.) for all kinds of problems. Rather, ambidextry is needed here.

For problems where the relationship between cause and effect is already known (complicated problem situations), the experts’ prior knowledge is sufficient to implement suitable solutions without having to experiment. Therefore, when teams have to write OKRs for issues such as the monthly payroll or regular security updates, there is rightly a feeling of “OKR theatre” among those involved.

On the other hand, teams rarely transparently visualise, prioritise, and measure their BAU. But using OKR to address only this deficiency is not cause but symptom treatment and should therefore be avoided. There are numerous other frameworks and tools that are suitable for managing recurring tasks or implementing known solutions, while OKR is suitable for validating hypotheses and learning in a complex environment.

Final thoughts

Basically, as it is often said: “All models are wrong, but some are useful”. If a framework is copied blindly without looking into it, rarely does anything good come out of it. To avoid “cargo cult”, the approach must be considered in a differentiated way in each individual context and designed accordingly.

When introducing OKR, but also other frameworks, it is important to first ask the question “What for? All those involved must be clear about what the framework is intended to help achieve or what problems are to be solved by OKR, by what the success of an OKR introduction can be seen and at what behaviour the participants should be alarmed.

If only one aspect of the entire OKR framework could be taken away, it would be outcome orientation, in order to work smarter, not harder, so that the focus is no longer on the quantity of work done, but on the outcome generated with the smallest possible investment.

If only one aspect of the entire OKR framework could be taken away, it would be outcome orientation, in order to work smarter, not harder, so that the focus is no longer on the quantity of work done, but on the outcome generated with the smallest possible investment.

Tweet

Reading tips

- Radical Focus – Christina Wodtke

- Outcomes over Output – Joshua Seiden

- Playing to Win – Roger L. Martin

- Good Strategy – Bad Strategy, Richard Rummelt

- North Star Playbook – John Cutler

- The 4 Disciplines of Execution – Sean Covey, Chris McChesney, Jim Huling

- Agile Retrospectives – Esther Derby, Diana Larsen

- High Output Management – Andy Grove